African Ranches Ltd: What Went Wrong?

Drawing lessons from the failure story of African Ranchers Ltd, the first private cattle ranching settlement established in Northern Nigeria

Highlights

The Great Forest

Millers Brothers

African Ranches Ltd

Ruga/Bounce

Footnotes

The Great Forest

Access to land is, by far, the most important thing when trying to create a ranch. After all, the purpose of a ranch is to raise livestock like cattle and sheep on a well-defined area of land.

So this must have been the reason why “the great forest” was seen as a fascinating place. Described as “a large area from Allargano northward to the Yobe river”1, it was any livestock farmer’s dream.

According to Derrick Stenning:

… for forty years [1850’s-1890’s] the ‘Great Forest’ was an ample, well-demarcated reservoir of immigrant Pastoral Fulani … large enough, well enough endowed, and sufficiently underpopulated to support the scale of pastoral immigration to which it was subjected without over-grazing becoming rapidly evident and necessitating further widespread southward or eastward migration.

In short, livestock farming was a vibrant activity in Northern Nigeria, and from 1900 Europeans wanted a part.

At the time, ranching was seen as a very profitable activity because of the dire need for beef in Britain, especially in the period after the first world war. Conversely, Fulani men in Northern Nigeria reared cattle in large quantities—creating a classic demand and supply situation.

A ranch in southwestern Nigeria

For instance, a certain Edward Braddon, a British engineer who had spent ten months in Nigeria wanted Lugard to grant him a land lease for “…not less than 2,400 square miles of grazing land…in blocks of not less than 400 square miles…within say 150 miles of present or projected Government railways”2.

And why did Braddon need 1.5 million acres3 of ‘Nigerian land’ to establish a ranch? You guessed right: he was interested in “opening up a new needed source of Beef supply for Great Britain…”.

The commercial logic was to buy cattle from Fulani men, herd them in a ranch for some time and send them to Lagos via a railway passing through a place in the North. From there, beef would find its way to England.4

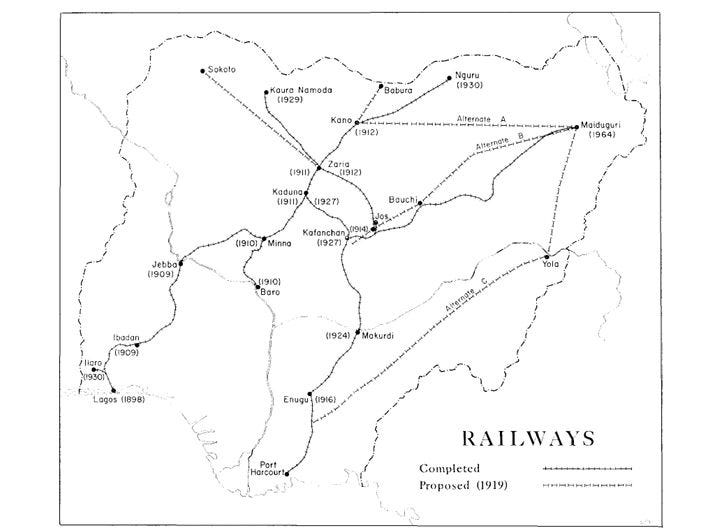

Rail network of colonial Nigeria

Braddon’s request for land was rejected, just like that of one Captain Griffith who petitioned the Colonial Office to grant him 100 square miles in the Kano province.

The prevailing position of the colonial government was to discourage private capitalism of native resources by Europeans, because of the rebellion that was witnessed in India, East Africa, and South Africa when indigenous people realized that colonialists were exploiting their local resources.5

But you know what happens when people of the same complexion keep asking themselves for things; one person eventually agrees. For “experimental and educational purposes”, Lugard agreed to grant leases for ranches to some of ‘his friends’ in the hope that, through ranching, “indigenous people” would learn how to ranch and tend to their livestock better.

According to Lugard:

foreign enterprise in ranching is generally already forestalled by the indigenous population and its cattle. In such districts, there is no room for the ranch properly so-called, but the European stock-breeder on a limited holding should not only be able to find profit, but by the object-lesson which his methods afford to the native, and by the purchase of surplus native stock, he may be of the greatest value to the country.

Millers Brothers

While Lugard aired6 Edward Braddon and Captain Griffith, he replied H.J Speed. Speed had asked for ranches before both men, requesting for a lease of 8 ranches for 99 years, consisting of 250,000 acres each. When he asked, Lugard countered, proposing to give him “one, or say two, ranches to be granted first as an experiment”.

The ranch was to be two square miles of 50 acres each, leased for only 21 years. Lugard also promised to give Speed access to more ranches if the first experiment proved successful.

But Speed didn’t get a piece of Nigerian land by praying, he got it through “connections”7. Speed worked with Millers Brothers of Liverpool, one of the most influential British trading companies in West Africa, and he had experience mining resources8 in Australia and Rhodesia9, all of which most certainly played into why he got land.

Speed and another merchant of Millers Brothers, A. A Cowan even countered Lugard’s counter-offer. Cowan replied to Lugard’s offer by requesting two ranches of 25,000 acres each, but Lugard gave a final offer of a thirty-six-year lease on two ranches of 12,500 acres each. The ranch was to be fenced, cleared, ploughed, and sown with good fodder grasses.10

After this, there were a few backs and forth between all the interested parties: H.J Speed and A. A Cowan of Millers Brothers, Lugard, who was Colonial Governor of Nigeria, and Lewis Harcourt, who was Colonial Secretary of the UK Government, but the agreement was largely concluded11.

Lugard granted rights to the Millers Brothers, in principle, to establish two ranches of 12,500 acres in Northern Nigeria, but added that the colonial government would have to “gauge the attitude of the Fulani and of the Native administration before it could agree to increase the areas or add a third or subsequent ranches”12.

[Read: Meet Viscount Harcourt]

African Ranches Ltd

The Miller Brothers incorporated African Ranches Ltd in July 1914. Speed had already started looking for suitable land for prospective ranches since the summer of 2013, and he had also started buying cattle in Borno and Kano provinces. Unfortunately, African Ranches Ltd began to face its startup challenges almost immediately: the inability of the Fulanis to guarantee a sale of a certain number of cows.13

While the Fulanis of Zaria only sold sick cattle or sold cattle when they needed to raise money to pay for the Jangali tax14, the Fulanis of Bornu and Adamawa were willing to sell cattle given the right amount. In any case, no rancher could predict the number of cows he was able to purchase from a Fulani herder, let alone even enter into a contract with him.

According to Dunbar15:

A demonstrated demand and steady market would result in an increase of sales. The chief difficulty would lie in getting the Fulani to contract to sell a specific number of cattle annually, a matter over which they could not, of course, exercise complete control.16

In short, then, the failure came in the attempt to establish a commercial relationship between seller and buyer and the inability of the former to produce a guaranteed annual surplus17, not because of any deep psychological attachment of the Fulani to their cattle. The Fulani are “economic men,” and their seemingly irrational behavior becomes comprehensible when one learns to appreciate the Fulani rationale.

In essence, Speed found a way to buy cattle for the ranch anyway, but the problem of shortage of cows for sale would come back to sink the ranch and the company.

The company set up two ranches in Rigachikun, Kaduna, and Allargano, Bornu areas respectively. But, by 1916, the Rigachikun ranch already began to experience a decline. Perhaps because of the first world war, or because H.J Speed died in 1916, the ranch declined to the point that the remaining 48 cattle on it were evacuated by 1917.

At the Allargano branch, things weren’t any better, even though E.J Speed replaced his brother in the management of the ranch. Although the total capacity of the ranch could only contain 800-1000 cows, there were more than 1,000 cows on the ranch to the point that cattle were grazing outside the ranch. In September 1917, it was estimated that 982 of the ranch’s 2,832 cattle grazed outside the ranch.

In his report of the ranch, G.J Lethem, the Assistant District Commissioner of the Area stated that in more than three years of occupance (sic) of the Allagarno site, the ranchers had made “. . . no far reaching undertakings towards improvement of fodder, water supply or breeding, . . . though certainly, they were keeping “. . . more cattle on a limited area than native owners would . . . and . . . with less labour”.

In essence, the ranch was poorly managed, and little had been done to improve the living conditions of the cattle on the ranch or the ranch itself.

E.J Speed and other merchants of Millers Brothers argued that they needed 500,000 acres of land to properly develop their ranching business and that it was only through access to more land and cattle that they could improve traditional livestock practices in Northern Nigeria.

But, any hopes of another land grant by the colonial government was dampened when the new colonial government of Hugh Clifford declared that “little has been done but what a Fulani cattle owner could have done under similar conditions”.

In his visit to the ranch in February 1920, Clifford noted that “the ranch and cattle were no more protected from rinderpest and other diseases than were native cattle”.

The government had given its final verdict: African Ranches Ltd had failed in modernizing traditional livestock practices in Northern Nigeria. It was doing the same thing the average Fulani cattle owner could and would have done.

By December 1920, the African Ranchers Ltd had all but fallen apart, especially since the colonial government was not impressed enough to grant the company its desired 500,000 acres of land.

The company agreed to sell the 1,422 cattle on its ranch to the government, but the deal never materialized. The company sold the cattle bit by bit, and in 1923, it tried selling 162 of the cattle to the Veterinary Department in Yelwa, along Sokoto, only to discover that 159 of them had contracted trypanosomiasis during the journey.

The ranch closed down in July 1924, African Ranchers Ltd ceased to exist as a company in 1931.

Ruga/Bounce

The story of African Ranchers Ltd is tragic at best, and at worst. Perhaps there’s also a little poetic justice about the evils of settler colonialism embedded in the story. But deep down, there are certainly lessons to draw, especially as it concerns recurrent farmers-herders clashes in Nigeria:

1) Livestock farmers and herders want access to land, and more of it. 2) Fulani herders need to upgrade their cattle breeding processes. 3) Finding land for herders and livestock farmers remains a big issue, since 1900. 4) Ranching remains a misunderstood subject, in Nigeria.

Just four lessons?

Derrick J. Stenning (1959). A Study of the Wodaabe Pastoral Fulani of Western Bornu Province. Pg 72

Gary S. Dunbar (1968). African Ranches Ltd., 1914-1931: An Ill-fated Stockraising Enterprise In Northern Nigeria. Pg 4

One mile of land is 640 acres

Gary S. Dunbar (1968). African Ranches Ltd., 1914-1931: An Ill-fated Stockraising Enterprise In Northern Nigeria. Pg 2

Siri, play “The Irony”

A slang in Nigeria which means to ignore

A slang in Nigeria which means influence

Actually, ‘exploiting’ (Okay, I’ll stop)

Modern Zimbabwe

Gary S. Dunbar (1968). African Ranches Ltd., 1914-1931: An Ill-fated Stockraising Enterprise In Northern Nigeria. Pg 5

Harcourt wanted the Millers Brothers to be given smaller 10,000-11,000 acres, but they refused

Gary S. Dunbar (1968). African Ranches Ltd., 1914-1931: An Ill-fated Stockraising Enterprise In Northern Nigeria. Pg 5

Gary S. Dunbar (1968). African Ranches Ltd., 1914-1931: An Ill-fated Stockraising Enterprise In Northern Nigeria. Pg 6

An annual cattle tax in Northern Nigeria

Gary Dunbar is a professor of

Emphasis mine

Emphasis mine

“Ranching remains a misunderstood subject, In Nigeria”

Nice article, maybe it should have a sequel.