Section 52(2): "Transmission, Transmission, Transmission"

The continuous obfuscation of democratic and electoral processes in Nigeria

Highlights:

Democracy — “Demonstration of Craze”

Townships Ordinance (1919)

Technology In Election

“We Have Capacity”

Footnotes

Democracy — ”Demonstration of Craze”1

As of the end of 2017, 96 out of 167 countries operated a democracy, while 21 out of those 167 countries operated an autocracy — according to the Pew Research Center.

A democracy, or a democratic system of government, is a system of government where all the citizens of a country control the affairs of the country, either directly or indirectly.

Because of the huge population of many countries2, it is impossible for all the citizens of democratic countries to “directly” control the affairs of their country. So, countries usually employ an “indirect” form of democracy.

If the people of a country decide to choose other people who will help them manage the country, then they prefer an “indirect” democracy. But for an indirect democracy to take place, there must be an election. After all, if three people want two different candidates to represent them in managing the country, the rational thing is for the three of them to vote for each of their preferred candidates — and the candidate with two votes should win, being in the majority.

Many indirect democracies, also called representative democracies, have elections periodically, usually every four or five years. And it is at these elections that new representatives are chosen.

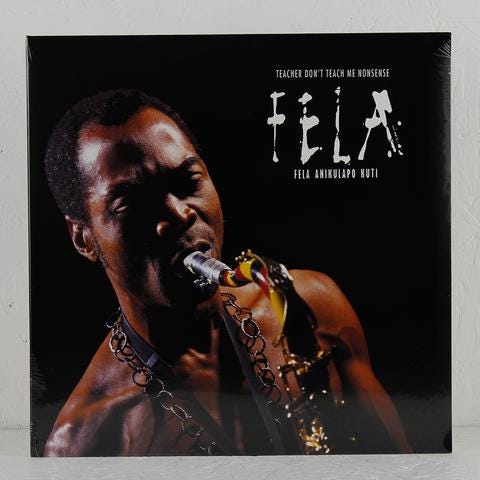

The cover for Fela Kuti’s 1986 LP, “Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense” — a studio album that critiques democracy in Africa.

Townships Ordinance (1919)

The process for the first “democratic”3 elections in any part of Nigeria was introduced in May 1919 when the Townships Ordinance No.29 of 19174 granted seats to three African men on the Lagos Town Council5. The election was conducted on March 29, 1920, and “the following people were elected: Mr A. Folarin (Lawyer), Dr A. Savage, and Mr G.D. Agbebi (Engineer)”6.

The British colonialists put together this law and legislative council perhaps in exchange for the power to impose township rates7, but still, democracy, or what seemed like it, forged on.

In 1922, Hugh Clifford, the colonial Governor of Nigeria from 1919-1925, introduced the “Clifford Constitution”. Under the constitution, there was a “Legislative Council”. 46 people were to make up the Legislative council,8 of which included 26 colonial officials as official members, 15 unofficial members, nominated by the colonial officers, and four elected “Africans”9. The four elected “Africans” were J.E. Egerton Shyngle, E.O Moore, Prince Kwamina Ata-Amonu, and Dr C.C Adeniyi-Jones10.

For any “African” to qualify to participate in the election, sex, nationality, age, residence, and income were very important considerations. For instance11, the prospective legislator must make a total annual income of not less than 100 British pounds during the calendar year before the date of the election.12

But clear laws always open up pathways. Following these laws, many literate Nigerians began to take an active part in colonial politics.13 On June 24, 1923, Herbert Macaulay founded the National Democratic Party (NDP) — the first Nigerian political party. The party won all the seats in the Legislative Council elections of 1923, 1928, 1933, until 1947.

In 1938, the Nigerian Youth Movement (NYM) ended the NDP’s dominance of the Lagos Town Council by winning the seats on the council, and in 1944, the newly formed National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) aligned with the NDP (now NNDP) to win all the three seats on the Lagos Legislative Council.14

Fela Kuti speaking and singing about the ills of democracy in Africa at the Midsummer concert of the Glastonbury Festival in 1984.

However, ever since the early years of the Lagos Town Council and the Legislative Council, Nigerians are yet to fully reap the “dividends of democracy”. There’s hardly any election that has been conducted since Nigeria's independence that was not involved in widespread election malpractice, fraud, voter suppression, and brazen abuse of power, and the democratic situation in Nigeria appears only to be getting worse, no thanks to power-thirsty politicians and gullible voters.

[Read: Is Tinubu Still Relevant?]

Technology In Election

On July 15, 2021, Sahara Reporters reported a story, “APC Senators Reject Electronic Transmission of Election Results”. The Electoral Act (Amendment) Bill 2021 had been presented before the Nigerian Senate, and in a majority vote, the Senate voted against the electronic transmission of results.

What happened was that the Senate Committee on INEC, through its chairman Kabiru Gaya, had presented the committee’s final draft of the Electoral Act (Amendment) Bill 2021 before the entire Senate for Third Reading, and a part of the amendment was seeking to make corrections to Section 52 of the Electoral Act (2010).

Note that Section 52 (2) of the Electoral Act (2010) reads:

The use of electronic voting machine for the time being is prohibited.

But under Section 52 (2) of the proposed Electoral Act (Amendment) Bill 2021, the Senate INEC Committee stipulated that:

The Commission may transmit results of elections by electronic means where and when practicable.

However, when the bill was presented before the Senate, a Sabi Abdullahi, an APC Senator representing Niger North, proposed that the clause should be amended to read:

INEC may consider electronic transmission of results, provided the national network coverage is adjudged to be adequate and secured by the Nigerian Communications Commission and approved by the National Assembly.

Some senators were against this clause while some others were for it, and the senators eventually put the issue to a vote. At the end of the voting, 52 senators, predominantly from the APC, voted in support of the clause while 28 senators, predominantly from the PDP, voted against the clause.

The senators who voted against the electronic transmission of results based their decision on a declaration by the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) that only 50 per cent of polling units in Nigeria have the 2G and 3G network needed for electronic coverage for electronic transmission of results.

At the House of Representatives, the situation was slightly different.

After a rowdy and inconclusive session on Thursday, July 15, 2021, the House finally concluded on Section 52 (2) Electoral Act (Repeal/Reenactment) Bill 2021 as drafted by its committee on INEC on Friday, July 16, 2021.

The retained clause read:

Voting at an election and transmission in this Bill shall be following the procedure determined by the Commission.

“We Have Capacity”

INEC Commissioner for Voter Education, Festus Okoye, speaking about the electronic transmission of votes

Amidst all of the political games, the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) itself has come out to say that it has the capacity for electronic transmission of results, even in remote areas.

Speaking on Channels TV, the INEC National Chairman and Commissioner for Information and Voter Education, Mr Festus Okoye said that:

We have uploaded results from very remote areas, even from areas where you have to use human carriers to access them. So we have made our position very clear, that we have the capacity and we have the will to deepen the use of technology in the electoral process.

But our powers are given by the constitution and the law, and we will continue to remain within the ambit and confines of the power granted to the commission by the constitution and the law.

In any case, electronic transmission of election results at the ward level should not have even been a contentious idea — it should have been warmly embraced.

According to Idayat Hassan, Director for the Center for Democracy and Development (CDD):

The electronic transmission will affect defects in the manual collation of results.

In every election, we have cases where collation officers are ready but there are no vehicles. Sometimes, they need generating set or they will not even know where to collate and these challenges muddle up the entire collation system.

It will eliminate interference by security agents, politicians and even thugs in the collation process. There will not be a reason to kidnap electoral officials and snatch ballot materials.

And another election observer, Eze Onyekpere of the Center for Social Justice agrees. According to him:

Results will be transmitted from where voting took place and everybody will witness it and there will be no manipulation. There will not be any need for collation centres.

So, if election observers and the electoral umpire all agree that electronic transmission of votes is a fool-proof method in ensuring the credibility of Nigerian elections, why don't the politicians think so?

Well, maybe Auwal Rafsanjani, Executive Director of the Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Center (CISLAC) is right:

With electronic transmission, there will not be any case of results missing on the way or snatching of ballot boxes…Any politician that does not want that to happen is planning to rig election.

Fela Kuti called Democracy a “demonstration of craze” in the 1986 LP “Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense”

For instance, Nigeria’s population is popularly reputed to be more than 200 million people. But how many venues can contain 200 million people?

The reader must distinguish between western democracy and indigenous democracy. If democracy is a system of government where people represent themselves or choose others to represent them, then it is hard to argue that democracy was not in place in many Nigerian areas before British colonialism, considering the way indigenous people in the Nigerian area loved and accepted their traditional political systems, and the extensive systems of checks and balances that were in place in those political systems.

This is ironic because the British annexed (or took over) Lagos in August 1861 by brute force and then proceeded to govern it by written laws. How convenient? These are the issues, but anyway.

The Lagos Town Council turned out to be a formidable political institution, and it went on to play host to some of the most notable Lagosians like Chief J.K Randle and Abubakar Ibiyinka Olorun-Nimbe.

Chapter 1, Representative Democracy In Nigeria [PDF]. Pg 2

Chapter 1, Representative Democracy In Nigeria [PDF]. Pg 2

Chapter 1, Representative Democracy In Nigeria [PDF]. Pg 2

So what “they” are telling us is that the people in Lagos didn’t exercise “democracy” before colonialism? And what kind of democracy includes only four indigenous people in a 46-member council, in their own country?

It appears clear to me that the history of “democracy” is flawed in Nigeria. Many of the “elected” representatives, who were lawyers and engineers, would hardly have become representatives of the people in pre-colonial Nigeria where leadership was often hereditary or was unanimously conferred. In this case, the “elected” representatives were literate elites who were rich, spoke the colonialist’s (English) language, and were chosen from an election that only involved men, among many other ‘artificial’ conditions!

Chapter 1, Representative Democracy In Nigeria [PDF]. Pg 2

You can draw a straight line between this law and how money came to dominate Nigerian politics.

You can draw a straight line from here to how politics in Nigeria came to be dominated by the elites. By imposing financial, educational, gender, and other barriers to taking part in governance, “ordinary” Nigerians lost government access, perhaps forever.

Chapter 1, Representative Democracy In Nigeria [PDF]. Pg 3

At the end of the day “Well, maybe Auwal Rafsanjani, Executive Director of the Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Center (CISLAC) is right:

“With electronic transmission, there will not be any case of results missing on the way or snatching of ballot boxes…Any politician that does not want that to happen is planning to rig election.”

Nice and educative write up as usual and one can draw a parallel as to where major problems in Nigeria politics stems from.